April, full moon. It is the Khmer New Year. The roaring of the locals’ boats floods out the night noises: the electronic music of the not so distant parties, the neighbor’s conversations, the small waves breaking against the bamboo rafts that keep households afloat.

Water hyacinths also gather in their own community, creating a parallel floating village that goes with the flow. They are like the Nothing in The Neverending Story, a dark and silent presence that becomes large at times before disappearing. But the water hyacinths never disappear before hindering the youth rowing from one party to another, or the fishers coming and going to and from the lake trying their luck at night fishing. To avoid the propellers of the boats getting tangled with the Nothing, they have to make their way over and over elevating the most possible the huge rod holding the propeller, which also increases the noise.

Tonle Sap, the largest lake in Southeast Asia, was formed 15,000 years ago. With the warming climate a river was born from the lake, connecting it to the Mekong, the “Mother River” of Southeast Asia, thus creating a unique ecosystem. The rivers of the Mekong are born in Tibet and run through Yunnan, Burma, Thailand and Laos. From November to May they flow into the sea, but in the monsoon they flush excess water in the lake, tripling its size. As the lake is only one meter deep at its center, the water makes its way back, surpassing the edge of the dry season. In October the water flows back again, and the lake empties back into the Mekong. This movement maintains a balance in the final stretch of the river, avoiding problems of flooding and drought. This balance involves a real lesson in impermanence. As one Cambodian proverb says, “When the water rises, the fish eat ants. When water is low, the ants eat fish.”

It is dry season, and the water level in Tonle Sap is low. The waters recede and enable the revenge of the ants. The low water also allow the locals to grow rice in areas that remain under water the rest of the year.

During the reign of Angkor Wat, founded five hundred years ago at the north of the lake, this annual flooding was of great importance. Yearly floods provided food to a population that reached half million, giving four crops of rice per year and providing the necessary animal proteins to more than 200 varieties of fish living in the lake. The stone reliefs at Angkor Wat show fish that local fishermen still recognize, demonstrating the enormous wealth that this ecosystem has maintained over the centuries.

This ecosystem also keeps various records: colonies of aquatic birds in danger of extinction and one of the most productive fisheries in the world, with an annual catch of 300,000 tons. This combination of natural resources makes the locals reluctant to abandon a way of life that has sustained them for centuries since the ancient and prosperous times of Angkor Wat, despite the immense poverty in which their lives are submerged.

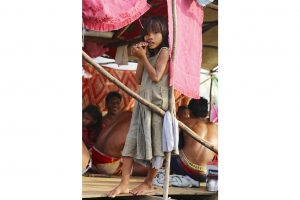

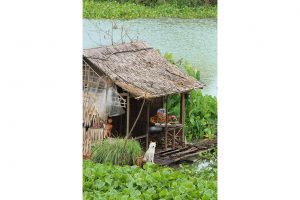

Currently about 80,000 inhabitants live in 170 floating communities, the solution that brings balance to a life somewhere between drought and flooding. Houseboats allow their necessary transfer, sometimes of several kilometers, of domiciles. Usually the man of the house responsible for dragging the house with ropes, with the whole family aboard. Some years the inhabitants are forced to move their entire home up to ten times.

Fishing is their main livelihood, done using various techniques for larger or smaller fish, also for the preservation of fish, essential in tropical climates. Other industries have emerged, such as breeding captive crocodiles for the exploitation of their skin, creating floating plots which supply the necessary vegetables, making handicrafts with the invasive water hyacinth stalks, and a tourism that is becoming more interested in this peculiar way of life.

Mothers must always keep their babies at arm’s length when the little ones are newly discovering the world around them they must pull on their clothing when crawling babies approach the house limits and the water. Their bodies are constantly rocked by water movements, and conversations are drowned out by the roar of passing boats. Children must wait all day within the limits of their homes, because the family has left with their only vehicle. They play with the dog, and none forgets to scan the horizon now and then, hoping their family members return soon.

Floating gardens; fishing farms; shops offering all kinds of products; the boat mechanic and the man who collects used batteries; the locals walking among undulating ships and platforms, without ever losing a step; a tiny boat with a dozen monks, all crammed in tight and sitting still lest they knock the boat over; the festival on the shore where they dance in circle the monotonous Khmer dance; trees in pots clinging with wires to the house posts; porches tuned up with party lights, or the inevitable furtive looks into the intimacy of the floating village, where privacy is difficult to maintain in a place where the houses have only one room that is everything, open to the river.

There are various excesses that threaten the livelihoods of locals and the habitat of Tonle Sap, as the exploitation of the vegetation of the area for construction or fuel, the poaching of protected birds or their eggs, the illegal fishing that undermines the variety and numbers of fish. But the greatest threat comes from the creation of dams and reservoirs on the upper Mekong river. These can irreversibly alter the cycle between the river and the lake, destroying the ecosystem of the area. The future of a lifestyle that has remained for hundreds of years depends on the administrative ability and the common sense of governments. How can we find the balance between progress and protection?